Avoiding generative AI (Gen AI) in the legal profession is now nearly impossible — it is everywhere. There is an abundance of articles explaining the benefits and risks of using tools such as Open AI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard or Microsoft’s Bing Chat. Despite the benefits of increased productivity and efficiency, the risks are at the forefront of everyone’s mind, especially hallucinations, where the model generates incorrect information. ChatGPT was in the spotlight in 2023 when an attorney used it for research and submitted a brief containing non-existent case authorities.

Consequently, courts, organisations and legal societies are increasingly issuing guidelines on using Gen AI in legal practice. In 2023, Judges in the US issued standing orders requiring the disclosure of Gen AI use and certification of efforts made to verify any factual representations and case authorities cited. Here in Australia, the NSW Bar Association issued guidelines stating that “barrister[s] should be transparent with clients about the use of AI tools and their use to assist in legal representations”. Some guidelines are broad in defining AI or not explicit about which technology to disclose. Should the use of tools like Grammarly, which improves grammar compliance, be disclosed?

These responses lead us to ask whether the impulse to regulate is an overreaction. We know many technologies come with benefits and risks in their use. So, why is Gen AI the focus of so much attention in the legal profession? I believe the omnipresence of Gen AI represents a broader dialogue on trust. Trust in the profession and trust in the technology.

Trust in the Profession

By way of background, James Shipton (chair of ASIC) in 2020 outlined three critical contributions to trustworthiness:

- Competence – having the right skills and knowledge to do the job.

- Care – attention and consideration applied to doing something correctly and avoiding risk, harm or damage.

- Ethics – doing the right thing, even when no one else is watching.

Unpacking these factors, it would be fair to say that the community expects lawyers to be specialists. They expect us to apply our skills, knowledge and experience when performing legal work. Notably, the community expects us to exercise our independent judgment. This includes the use of technology — and for us to know how to use it responsibly.

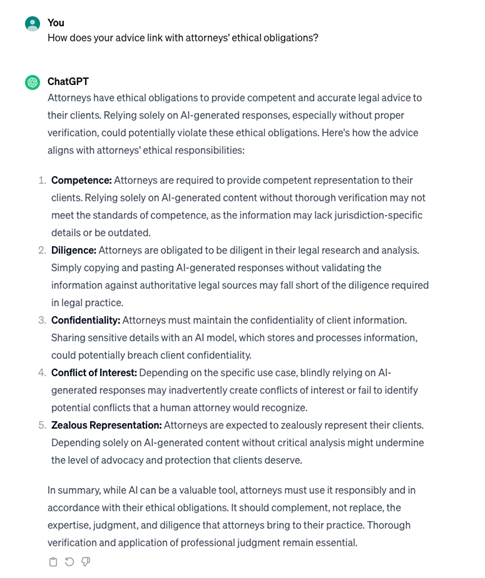

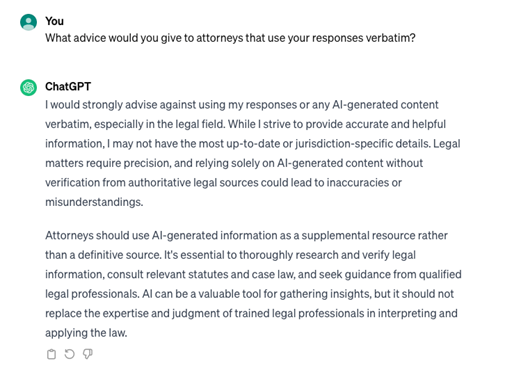

The hallucinations produced by Gen AI raise concerns about the tool's reliability and can have a notable effect on the reputations of lawyers who lack comprehension of the underlying algorithmic models. Known limitations should be understood. Tools like ChatGPT may not indicate where there is insufficient data to produce an answer (unless asked directly; see below using ChatGPT4). Care needs to be taken to determine whether Gen AI is appropriate for a task and where used outputs are carefully checked and interrogated.

The hallucination examples in Mata v Avianca and another, more recently, in the Matter of Samuel, reminded us of our ethics and professional responsibility. Gen AI was used when users were pressed for time or under pressure to produce a document. However, not understanding how the tool works or its limitations can increase the threat of creating an inaccurate document.

Any use of Gen AI in practice must be consistent with our pre-existing ethical obligations. The opening to Castel’s sanctions opinion in Mata v Avianca captures this: “Technological advances are commonplace, and there is nothing inherently improper about using a reliable artificial intelligence tool for assistance. But existing rules impose a gatekeeping role on attorneys to ensure the accuracy of their filings.”

One criticism of introducing the standing orders in the US to declare and certify is that they impose obligations that already apply under existing ethical rules. The penalties applied in Mata and Samuel do publicise a cautionary tale against the premature use of Gen AI. The penalties, however, were primarily for disregarding the pre-established professional conduct rules.

The issuance of orders, rules or guidance on Gen AI use acts as a reminder to follow conduct rules against the backdrop of technological change. To do so demonstrates a collective commitment to serve the public interest and deliver a public good. For our profession to be effective, we must maintain the community’s trust. Our conduct and ethical rules help maintain this trust. Being mindful of our professional obligations before using Gen AI tools is crucial and not breached in the event of such use.

Trust in the Tech

The use cases of Gen AI in legal practice will likely increase in 2024. The genie is out of the bottle, considering lawyers already use Gen AI to summarise documents, conduct research, and draft legal or marketing material.

The issuance of orders, rules, or guidance on Gen AI could also be a reflection that, at times, we have misplaced our trust in this tool’s current iteration. But what does it take for one to trust Gen AI?

Trust is a critical aspect of adopting and using any technology. Many factors can influence a tool’s trustworthiness to a user. One definition of trust in AI is the ‘tendency to take a meaningful risk while believing in a high chance of positive outcome’.

An AI system’s trustworthiness is heavily dependent on how the user perceives it in terms of technical characteristics. The accuracy, reliability, completeness, and currency of the data used to train the model are crucial in establishing trust in the system. Users will consider the potential risks and benefits, which can affect their trust in the technology. The form of an AI system (for example, in a chatbot) and its capabilities are important precursors to developing trust. Even its graphical user interface can influence the trustworthiness of its outputs.

Ultimately, we want AI systems to be transparent and explainable. Each must have the capability, functionality and features to do what is expected. Once Gen AI exhibits these qualities, we will be more confident using it, which can lead us to save considerable resources. This may then lead to a redefinition of trust with the technology used in human-AI systems.

But what do we do with the current limitations of Gen AI, the inaccuracies it produces, and its growing use in the legal community? Arguably, this offers an opportunity for the profession. The wider publicity of its limitations and spectacular failures engages us to examine Gen AI — generating inquiry about how it works, understanding what data a model is trained on and how to use the tool effectively. We should not shy away from it. Lawyers instinctively want to know where information comes from — it is, after all, a skillset instilled in us from law school.

Discussing and understanding how the tool works and can be used will benefit us all in the long term. Once our understanding increases (lawyers and society), any standing orders to verify and certify will likely disappear into the ether. Alternatively, Gen AI will adopt product standards that lead to it being fit for purpose. Ultimately, these discussions are a good thing, and we need to keep having them as the tech continues to evolve. It demonstrates a shared ethical culture that underpins our commitment to serve the public interest and a commitment to adapt so we can continue to do that well.

About the Author

Mitchell Adams is a senior lecturer at Swinburne Law School and a CLI Distinguished Fellow (Emerging Technologies) with the Centre for Legal Innovation (CLI). His specialisation lies at the intersection of law and technology, as an expert in intellectual property law, legal tech and legal design. Mitchell heads up the Legal Technology and Design Clinics at Swinburne Law School, where he creates the conditions for legal innovation through student and industry collaboration. As a CLI Fellow, Mitchell is working on developing education opportunities in prompt engineering for Gen AI and a framework for the classification of legal Gen AI.