An integral part of the Ninian Stephen Law Program has been the publication of the New Legal Thinking for Emerging Technologies report.[1] Specifically, the report found that there was a lack of recognition as to the value of lawyers in the face of emerging technologies, that there was an existing skills gap regarding emerging technologies, and that there is a need for technological education within the legal sector. This paper identifies additional questions, responding to those findings. Questions are asked as to how the role of the lawyer – and specifically the junior lawyer – will change in the face of AI, and how to best deliver technological education to law school students.

1. Scene setting

How are law schools adjusting to Generative AI?

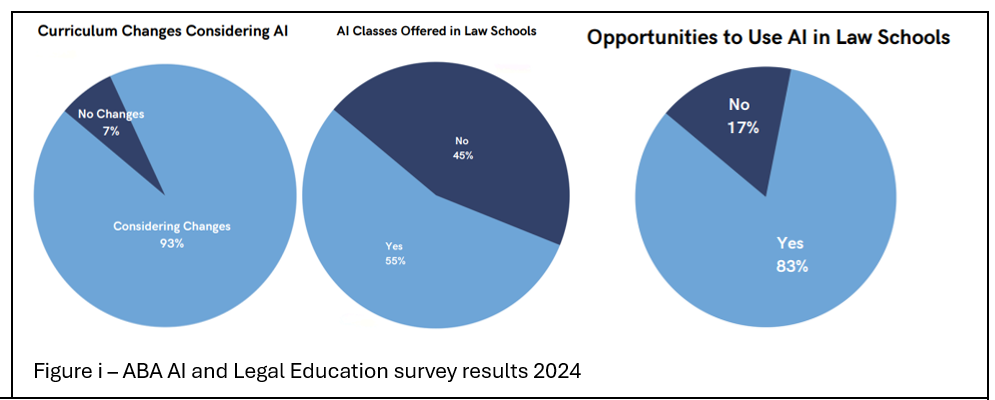

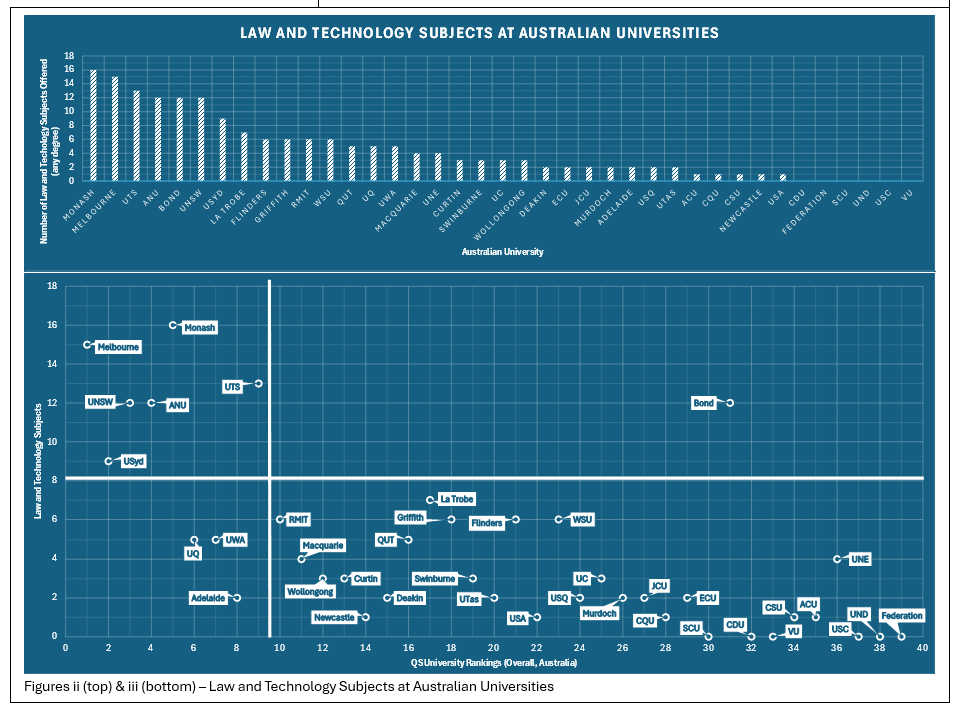

In late June 2024, results from a survey of American law school deans by the American Bar Association (ABA) were published. The results indicated a high level of enthusiasm and AI-uptake in law schools (Figure i).[2] In Australia likewise, 86% (32/37) of public universities offering a law degree [3] offer at least one law and technology subject (Figure ii).

While these subjects may not exclusively cover AI, it is nevertheless clear that law schools in Australia and the US are adjusting their syllabuses to teach students about AI and the law.

In Australia, there appears to be some correlation between university rankings and the number of law and technology subjects offered (Figure iii), in that the universities offering several law and technology subjects happen to be higher ranking universities (except for the only private university included, Bond University). This is not to claim there is a causal relationship between these variables, another way of understanding the relationship is by reference to size.[4] In any event the takeaway is that tech subjects are unevenly distributed across universities.

It is reasonably uncontroversial that law schools should be teaching students about how AI interacts with the law, though there is much scope for debate about how and where this is located in the curriculum. Questions, however, are raised when law schools teach students how to use AI to do legal research and writing. Key concerns are that students will perform worse on upcoming bar exams, lose key critical thinking skills, and be unprepared to deliver justice. These issues are partly influenced by the use of new technologies, including generative AI in law firms, courts, and other areas of legal practice.

How is legal practice adjusting to Generative AI?

The legal profession has been making use of advances in digital technology for some time,[5] including, in particular, technology-assisted document review [6] and contract automation tools, along with research and precedent management technologies.[7] Large law firms and legal information providers have increasingly become interested in using generative AI to improve the efficiencies and the quality of core legal work.[8] A survey by Thomson Reuters in April 2024 of professionals in Asia (including Australia) indicated that ‘64% of professionals expect that artificial intelligence will be transformative or have a high impact on their profession’.[9] They have rapidly been trialling possible uses of generative AI in legal tasks such as legal research, and summaries/synthesis.[10] Existing established technology use cases, such as document review, are being adapted to incorporate the new capacities of generative AI.[11]

Various generative AI applications are being made available to lawyers as tools for performing substantive legal tasks through the primary legal publishers. [12] Law firms can purchase bespoke generative AI tools built from ChatGPT through Harvey.[13] Australian law firms have also been experimenting with developing their own AI tools.[14]

Courts and tribunals have been slower and more cautious in exploring the use cases for generative and other advanced forms of AI.[15] Nonetheless, it seems inevitable that judges and courts will make use of advances in AI, and including generative AI.[16] Some courts have already expressed support for these possibilities. Thus, for example, Sir Henry Vos, Master of Rolls, has described the use of AI for some tasks, and with adequate safeguards, as ‘inevitable and useful’.[17] Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon of the Singapore Supreme Court has commented that:

If used properly, AI can be a tremendously useful assistive tool that can improve the quality of decision-making and enable judges to surpass ordinary human limitations. Indeed, AI may prove to be indispensable in dealing with the increasing technical, evidential and legal complexity that we see in many categories of disputes today.[18]

2. Questions for legal training

Why are junior lawyers concerned about Generative AI?

While the legal profession has experienced periods of digital transformation before, such as with the introduction of online databases for legal research,[19] law has long been relatively unaffected by technological change, unlike more mathematical or technical disciplines. Generative AI (GenAI), however, is believed to change this. As put by technology lawyer Damian Riehl: “Law’s foundation is built upon words … and it turns out that Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT are designed to excel at understanding and generating words.”[20]

Open AI’s ChatGPT-4 has been described by University of Colorado Law Professor Harry Surden as “capable of producing a good first draft of a legal motion”.[21] Professor David Wilkins, director of the Centre on the Legal Profession at Harvard Law School, goes as far as to say that ChatGPT can produce a memo about a legal question which is “approximately as good as what a first-year law firm associate would produce.”[22] While Surden and Wilkins acknowledge that AI-written documents would require editing, the same can be said about the legal writing of many junior lawyers. The most significant difference for law firms, is that GenAI takes a fraction of the time, and costs a fraction of the price of a junior lawyer.

Thus, law firms with an interest in remaining competitively efficient are expected to restructure in the coming years, by reducing the number of junior lawyers and paralegals, and having GenAI write legal briefs and do legal research.[23] This raises concerns for junior lawyers, but also for the legal industry. Will enough junior lawyers get the experience to become senior lawyers if law firms restructure? If GenAI replaces the work of junior lawyers, how will junior lawyers learn the crucial legal writing and research skills expected of senior lawyers?[24]

Or perhaps this is catastrophising. Firms may provide training and even semi formal certification to trainee lawyers to become skilled in the firm’s choice of AI and software products. CLE, and possibly compulsory CLE on technology literacy, may fill the gap.

Another suggestion is that the role of junior lawyers will be redefined to be more focused on the monitoring of AI-produced content.[25] These debates have also extended into the realms of legal education, as law schools adapt and adjust to the challenges and promises of GenAI.

Key Questions:

- What does the future of law look like for junior lawyers, paralegals, and law school graduates?

- If most junior lawyering work of the future is likely to be ‘editing AI’, will this provide junior lawyers with the learning experiences required to develop strong legal reasoning, critical thinking, and strategy skills?

- Where will this necessary career development come from?

- What kinds of continuing education for lawyers would adequately respond to technological innovation?

3. How should law schools be adjusting to Generative AI?

AI in Legal Practice

As explained earlier in this paper, AI tools are believed to be currently capable of producing work at least at the level of a junior lawyer. Thus, law firms with an interest in remaining commercially competitive are likely to begin using GenAI to complete work at a very low cost, work for which they would usually need to pay a junior lawyer. While law firms may restructure, they will not stop hiring junior lawyers (but they made reduce how many are hired). Instead, what is reasonable to expect is that junior lawyers will be working with AI, such as checking and validating AI output.[26] Given this prediction, it is assumed that law schools should be teaching students the skills required to work with AI – such as prompt engineering – in order to generate high quality AI content, alongside the skills required to conduct legal research – such as using legal databases – in order to validate AI output. However, some scholars are critical of teaching students to use GenAI; this is a contentious issue.

The NextGen Bar Exam

Beginning in July 2026, the (US) National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE) will roll out the NextGen Bar Exam. The NextGen is expected to evaluate legal research and writing skills to a greater extent than the current bar exam, to ensure that graduates have practice-ready skills.[27] However, this raises concerns for students who have become dependent on GenAI to do their writing and research, as discussed by University of North Dakota Assistant Professor of Law Carolyn V. Williams.[28]

Williams presents three scenarios, students taught by traditionalist professors, students taught by future-thinking professors, and students taught by balanced professors. Williams sees the first two approaches as problematic. In the case of traditionalist professors, who disregard GenAI and forbid its use, many (lazy) students will use it anyway, unbeknownst to the professor, and will grow dependent on GenAI to do legal writing work. In the case of future-thinking professors, who wholeheartedly encourage GenAI usage (as that is what mirrors/will mirror practice), many students will also grow dependent on GenAI to do legal writing work. As long as there is a NextGen Bar Exam to pass, requiring students to do complex legal writing tasks, students cannot be allowed to grow dependent on GenAI to an extent that they cannot competently complete legal writing tasks independently.

Williams argues that the solution here is in the way students are assessed. Regardless of the extent to which a professor wants students to engage with GenAI, the balanced approach requires assessments to be structured to ensure that students are gaining the crucial legal writing skills without growing dependent on GenAI.[29]

Soft Skills – Critical Thinking and Client-Centred Lawyering

While AI is often predicted to replace many of the hard skills involved in lawyering – such as legal research and writing tasks – AI is not expected to replace lawyers completely. The judgement calls, intuition, case strategy and overall critical thinking expected of lawyers both come from life experiences and rely on empathy in a way that AI is not expected to be able to match.[30] In a similar way, the skill of client-centred lawyering (CCL) – actively viewing legal problems from each client’s perspective[31] – is a skill which is thought to differentiate lawyers from AI. Crucially GenAI is also unable to replicate the exercise of ethical judgment that is critical to the delivery of competent legal services.[32]

Thus, it seems crucial that these soft skills are emphasised in law schools, to differentiate legal graduates from GenAI software (while acknowledging that this is for many reasons a terrifying sentence). Some scholarly research, however, suggests that the use of GenAI tools can cause students to lose the ability to think critically and deliver CCL. Professors Jonathan H. Choi and Daniel Schwarcz’s recent study of student exam performance with and without AI-assistance demonstrated that, while low-performing students tended to perform better with AI-assistance, previously top-performing students tended to perform worse when AI-assisted. Two proposed reasons for this are that top students were either misled by GenAI hallucinations, or struggled to integrate AI and human responses into one coherent essay.[33] The hallucination problem is an inventible aspect of GenAI, even though RAG and finetuning may improve accuracy. Moreover, even aside from accuracy, the integration concern remains. A worry is that, when students are presented with (correct) AI answers, their own ability to think critically about a case, spot hidden issues, and consider rule variation implications may be crowded out, meaning they end up with an essay which is not incorrect, but doesn’t show a high level of legal critical thinking.[34]

Further, NYU Law Fellow Jake Karr and NYU Law Professor Jason Schultz argue that GenAI is incompatible with CCL. Karr and Schultz argue that CCL requires one to have a relationship with clients built around dynamic interactions, where lawyers ask as many questions of their clients as they answer. A lawyer utilising CCL would be expected to ask clients about their specific circumstances, to deliver tailored advice and legal strategy. Current GenAI lacks the capability to ask questions clarifying what was asked of it and appears a long way from building the kind of relationship with clients which is required to deliver CCL.[35] Thus, multiple concerns are raised that integrating GenAI into law school classrooms will inhibit students’ efforts to gain the crucial soft lawyering skills especially required in the age of GenAI.

Justice Readiness

Karr and Schultz also discuss the skill of justice readiness, something they believe law schools must teach students. Justice readiness is the ability of students to understand right from wrong, and then to use the law for ‘good’ and to promote positive change. Karr and Schultz fear that GenAI systems – being racially biased, environmentally damaging, and controlled solely by wealthy technology companies – may distort students’ abilities to understand right from wrong. It is also feared that, given GenAI systems rely solely on past data, they may lack an ability to promote positive change. Instead, it is feared that GenAI tools will simply exacerbate existing inequalities. Given the power of law, Karr and Schultz consider it imperative that law students are discouraged from using GenAI in legal practice, and instead are taught justice readiness, to become forces for good.[36]

Overall

Overall, while there is an understanding that law practice will more likely than not involve GenAI usage, there is debate as to whether it is appropriate to teach legal GenAI skills in law schools. There are fears that GenAI could limit critical thinking, as well as client-centred lawyering and justice-readiness skills, and thus that law schools should focus on teaching these, letting students learn GenAI skills once they begin working. However, if law schools are expected to produce ‘job-ready’ graduates, and if GenAI is part of the job, then it could be argued that law schools should be teaching it.

Yihan Goh J of the Singapore Supreme Court (and former Dean of Singapore Management University) has suggested that:

law schools must continue to train students in three areas: (a) engage in high-level critical analysis; (b) provide creative solutions to complicated problems; and (c) provide emotive client-focused representation. These three areas require students to integrate knowledge from different disciplines to provide creative solutions to important contemporary problems.[37]

Further “there needs to be instruction on how to use AI within the legal field, much like how LexisNexis and Westlaw are already integrated into legal education.”[38]

Key Questions:

- How should law schools (and/or PLT) redesign assessment to better prepare students for AI-assisted practice

- Should law schools teach AI skills – if so, what skills? And how?

- Should law schools offer opportunities for training in practical AI skills for ‘legal’?

- Should law schools be looking to incorporate GenAI into the curriculum, and how?

- Would teaching GenAI realistically impact junior lawyers’ critical thinking, CCL and justice readiness?

Conclusion

This post was originally prepared as a discussion paper for an August 2024 Roundtable conducted by the Centre of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ethics at the University of Melbourne Law School, under the Ninian Stephen Law Program, powered by the Menzies Foundation. The questions posed were used to stimulate an engaging conversation between representatives from across the legal industry, including educators, practitioners, regulators, legal-tech developers, and legal industry think tanks.

The information provided in this post and outcomes of that Roundtable session will be used to create a White Paper on the topic of Generative AI and Legal Education. If you would like more information about this White Paper, or have interesting thoughts on the topic of Generative AI and Legal Education, feel free to contact Oli Nassau via his email o.nassau@unimelb.edu.au.

About the Author

Oli Nassau is a Research Assistant at the Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ethics (CAIDE). Oli is currently completing his Bachelor of Arts at the University of Melbourne, double-majoring in Philosophy and the History and Philosophy of Science (HPS). He has a passion for difficult questions, possible futures, and the intersections of humanity and emerging technology. Oli plans to study the Juris Doctor at Melbourne Law School, and he hopes that there is still a place for junior lawyers in the legal industry by the time he graduates.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges the contributions to this paper of his supervisor, Professor Jeannie Marie Paterson and extends his thanks to Jeannie, Professor Julian Webb, and Terri Mottershead for their assistance in presenting and publishing it.

The Centre for Legal Innovation gratefully acknowledges the permission granted for re-publication from the author and the Centre of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ethics at the University of Melbourne Law School.

--

Endnotes

[1] Fahima Abedi et al., New Legal Thinking for Emerging Technologies (Report, 2023) <https://www.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/4899916/Ninian-Stephen-Law-Program-New-Legal-Thinking-for-Emerging-Report-March-2024-final.pdf>.

[2] Cynthia Cwik, Bridget McCormack, Andrew Perlman & Joseph Gartner, ‘AI and Legal Education Survey Results’, American Bar Association (online, 2024) <https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/office_president/task-force-on-law-and-artificial-intelligence/2024-ai-legal-ed-survey.pdf>.

[3] Federation University (public) are excluded due to only offering a Bachelor of Criminology and Criminal Justice, not a LL.B., JD or LLM. Bond University (private) are excluded from the 37 public universities, but included in Figures iii & iv due to offering an extensive number of law and technology subjects.

[4] Other variables such as size of cohort and metropolitan vs regional location may also have explanatory power.

[5] See Michael Legg and Felicity Bell, Artificial Intelligence and the Legal Profession (Hart Publishing, 2020); Julian Webb, ‘Legal Technology: The Great Disruption?’ (2022) 2 Lawyers in 21st-Century Societies 515 <https://doi.org/10.5040/9781509931248.ch-022>.

[6]Indeed, courts in the United States, Ireland, England and Wales, and Australia have approved the use of TAR in the litigation process: Lyria Bennett Moses, et al., AI Decision-Making and the Courts: A Guide for Judges, Tribunal Members and Court Administrators (Report, 2022) 16 <https://aija.org.au/publications/ai-decision-making-and-the-courts-a-guide-for-judges-tribunal-members-and-court-administrators/.>

[7]See Thomson Reuters, Tech and the Law Report (2023) 19.

[8] See CAIDE Summary of Law Firm Promotion of Generative AI use (forthcoming).

[9] Thomson Reuters, Future of the Professions Report (2023) 5.

[10] Thomson Reuters, Generative AI for Legal Professionals (Report, 2024) 8 <https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/content/dam/ewp-m/documents/legal/en/pdf/white-papers/tr4105802.pdf>.

[11] See CAIDE Summary of Law Firm Promotion of Generative AI use (forthcoming).

[12] See, e.g., Casetext, ‘Casetext CoCounsel’ <https://casetext.com/cocounsel/>; LexisNexis, ‘Lexis+AI’ <https://www.lexisnexis.com.au/en/products-and-services/lexis-plus-ai>.

[13] Harvey <https://www.harvey.ai/>. Also https://www.allenovery.com/en-gb/global/news-andinsights/news/ao-announces-exclusive-launch-partnership-with-harvey; Sara Merken, 'UK law is latest to partner with legal AI start-up Harvey’ Reuters (September 22, 2023); <https://siliconangle.com/2023/03/15/pwc-partners-harvey-build-ai-tools-assist-lawyers/>.

[14] Noah Yim, ‘Australia’s biggest law firm, MinterEllison, is using a version of ChatGPT for its first draft of some legal advice’, The Australian (online, 4 Dec 2023) <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/australias-biggest-law-firm-minterellison-is-using-a-version-of-chatgpt-for-its-first-draft-of-some-legal-advice/news-story/517fe2e4ea2371b62ac69ce75aecd66a>.

[15] For a comprehensive discussion of automation and AI in courts, including generative AI in Australia see Lyria Bennett Moses et al., AI Decision-Making and the Courts: A Guide for Judges, Tribunal Members and Court Administrators (The Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Inc, December 2023).

[16] See also Monika Zalnieriute and Felicity Bell, ‘Technology and the Judicial Role’ in Gabrielle Appleby and Andrew Lynch (eds), The Judge, the Judiciary and the Court: Individual, Collegial and Institutional Judicial Dynamics in Australia (Cambridge University Press, 2021) 116, observing a move from digitiasation (eg e-filing) to the automation of court functions.

[17] James Titcomb, ‘Judges given green light to use ChatGPT in legal rulings’, Telegraph (online, 12 December 2023) <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2023/12/12/judges-given-green-light-use-chatgpt-legal-rulings/>.

[18]Sundaresh Menon, ‘Judicial Responsibility in the Age of Artificial Intelligence’, (Speech, Inaugural Singapore-India Conference on Technology, 15 April 2024).

[19] Olga Mack, ‘The Digital Transformation Journey: Lessons For Lawyers Embracing AI’, Above The Law (online, 26 April 2024) <https://abovethelaw.com/2024/04/the-digital-transformation-journey-lessons-for-lawyers-embracing-ai/>.

[20] Damien Riehl, 'We Need to Talk about ChatGPT: A Lawyer's Introduction to the Exploding Field of AI and Large Language Models' (2023) 80(4) Bench & Bar of Minnesota 26.

[21] Ronald M. Sandgrund, 'Who Can Write a Better Brief: Chat AI or a Recent Law School Graduate? Part 1' (2023) 52(6) Colorado Lawyer 24.

[22] Jeff Neal, ‘The legal profession in 2024: AI’, Harvard Law Today (online, 14 February 2024) <https://hls.harvard.edu/today/harvard-law-expert-explains-how-ai-may-transform-the-legal-profession-in-2024/>.

[23] Tom Shepherd and Stephanie Lomax, ‘Generative AI in the legal industry: The 3 waves set to change how the business works’, Thompson Reuters (online, 27 February 2024) <https://www.thomsonreuters.com/en-us/posts/technology/gen-ai-legal-3-waves/>.

[24] Baljinder Singh Atwal, ‘How will AI impact junior lawyers?’, Legal Cheek (online, 5 January 2024) <https://www.legalcheek.com/2024/01/could-robots-replace-junior-lawyers-2/>.

[25] ‘How Is AI Changing the Legal Profession?’, Bloomberg Law (online, 23 May 2024) <https://pro.bloomberglaw.com/insights/technology/how-is-ai-changing-the-legal-profession/#will-ai-replace-lawyers>.

[26] ‘How Is AI Changing the Legal Profession?’, Bloomberg Law (online, 23 May 2024) <https://pro.bloomberglaw.com/insights/technology/how-is-ai-changing-the-legal-profession/#will-ai-replace-lawyers

[27] Catherine Fregosi, 'Change in the Legal Writing Classroom: The NextGen Exam and Generative AI' (2023) 49(3) Vermont Bar Journal 13.

[28] Carolyn V Williams, 'Bracing for Impact: Revising Legal Writing Assessments ahead of the Collision of Generative AI and the NextGen Bar Exam' (2024) 28 Legal Writing: The Journal of the Legal Writing Institute 1.

[29] Carolyn V Williams, 'Bracing for Impact: Revising Legal Writing Assessments ahead of the Collision of Generative AI and the NextGen Bar Exam' (2024) 28 Legal Writing: The Journal of the Legal Writing Institute 1.

[30]Jodie Cook, ‘Will AI Replace Lawyers? Entrepreneurs Share Their Predictions’, Forbes (online, 15 February 2024) <https://www.forbes.com/sites/jodiecook/2024/02/15/will-ai-replace-lawyers-entrepreneurs-share-their-predictions/>.

[31] Jake Karr and Jason Schultz, 'The Legal Imitation Game: Generative AI’s Incompatibility with Clinical Legal Education' (2024) 92(5) Fordham Law Review 1867.

[32] Sherman J Clark, ‘Work Only We Can Do: Professional Responsibility in an Age of Automation’, (2018) 69(3) South Carolina Law Review 533.

[33] Jonathan H Choi & Daniel Schwarcz, 'AI Assistance in Legal Analysis: An Empirical Study', (2023) 73 Journal of Legal Education (forthcoming, 2024).

[34] Catherine Fregosi, 'Change in the Legal Writing Classroom: The NextGen Exam and Generative AI' (2023) 49(3) Vermont Bar Journal 13.

[35] Jake Karr & Jason Schultz, 'The Legal Imitation Game: Generative AI’s Incompatibility with Clinical Legal Education' (2024) 92(5) Fordham Law Review 1867.

[36] Jake Karr & Jason Schultz, 'The Legal Imitation Game: Generative AI’s Incompatibility with Clinical Legal Education' (2024) 92(5) Fordham Law Review 1867.

[37] Goh Yihan, ‘Artificial Intelligence in Judicial Training and Education: Potential Use of Artificial Intelligence in Training and Education of Judges, (Speech, Inaugural Singapore-India Conference on Technology, 15 April 2024).

[38] Goh Yihan, ‘Artificial Intelligence in Judicial Training and Education: Potential Use of Artificial Intelligence in Training and Education of Judges, (Speech, Inaugural Singapore-India Conference on Technology, 15 April 2024).